21 Jul The Shows that Mattered, Part I

And now, Gentle Reader(s), for something perhaps not completely different, but somewhat different nonetheless. I have been ruminating upon the concerts that I have attended in the ebb and flow of my approximately 21,000 Days on Earth and have decided to give you a breakdown of the ones that had the most impact on me in terms of my enjoyment, enlightenment, and overall significance. My presence at some of these events was carefully planned in advance and in others instances the result of spontaneous decisions or pure happenstance. Some of these shows took place in arenas and vast halls and others were in tiny venues with a bare handful of people in attendance. One way or the other, these are the shows that made a significant impression at the time and have stuck with me over the many years. It’s a pretty wildly diverse collection of performances but that’s the way Your Humble Narrator rolls, yo.

I give you The Shows That Mattered, Part the First:

New Orleans, circa spring, 1977

This was an overcast Friday afternoon in spring of 1977 when I was a student at Benjamin Franklin Senior High in New Orleans—a lad of 17 years. Despite my tender age I had been a dedicated barfly at music establishments around town for a couple of years. The drinking age in Louisiana was 18 at the time, and no one really gave a shit anyway.

On this particular occasion the Meters were set to play an outdoor concert from the back of a flatbed truck parked on Broadway in front of the longstanding Tulane University watering hole, the Boot, above which was the city’s grooviest record store and head shop, the Mushroom. Amazingly, both establishments exist in these very same locations to this very day. Anyway, after school let out (or a bit before) a group of my classmates and I walked over to the Boot to catch the show. The skies were threatening and, sure enough, rain began to pelt down as the advertised concert hour approached. Everybody crowded into the Boot and the Meters’ equipment was hauled down off the flatbed and set up inside. It was packed shoulder to shoulder and after an hour or so of delay the band began to play. I can’t remember much about the specifics of the show but they were loose and tight and wild and incredibly funky and EVERYBODY was dancing like an absolute mad person. The Meters could lay down a groove so solid that you could build a skyscraper on top of it. These cats (with the exception of Cyrille, who joined the original four-piece in 1970) had been mainstays of the local club and studio scene since 1965 and they were universally acknowledged as the best—the most badass funk machine in a town that lived and breathed funk. The gig at the Boot this afternoon featured the classic five-piece lineup of Art Neville on vocals and keys, younger brother Cyrille on vocals and congas, Zigaboo Modeliste on drums, George Porter on bass and Leo Nocentelli on guitar in the last days before the Meters disbanded (or at least regrouped with a different keyboardist and lead vocalist) and the Neville Brothers were born.

The most distinct image I retain from this event is my classmate Frith dancing atop a pinball machine with a huge smile on her face. This sort event more or less encapsulates my young life in and around the incredibly fertile music scene of New Orleans in the mid/late 1970s. It was one of those moments of pure, unalloyed joy—all the more so as it was free and impromptu. The Meters were a high water mark (dangerous analogy, that) in the New Orleans music scene and their fifth studio album, Rejuvenation from 1974, remains very near the top of my list of greatest albums of all time. Certainly within the top ten by any New Orleans artist. Make that top five. Okay, let’s just say it’s Number One.

The Neville Brothers at Tipitina’s

The Neville Brothers at Tipitina’s

New Orleans circa 1978

Back in the day, I saw the Nevilles perform at Tipitina’s more times than I can possibly recall. They were a regular Friday or Saturday night presence at this legendary nightspot, which was more or less my neighborhood bar—it was less than a five minute bike ride from Inky Home on the uptown edge of the Irish Channel. I was such a regular at Tipitina’s that on most nights the doorman, the much beloved Stanley John (whose photo, hefting an approximately 300 lb engine block in his massive arms, adorned the wall next to the front door) just waved me through. My classmate Sonny was the soundman at Tip’s and I often spent part of my evenings next to him in the elevated platform on the left side of the room. Dixie longnecks were .75¢ apiece and the cover charge (if you had to pay it) maxed out at $5 on weekends. You could make a full night of it on $10, tipping included.

The dissolution of the Meters was a shock to us all but when the Nevilles arose from the ashes any hesitation we had was quickly dispelled. Zigaboo and George and Leo were hard to replace but the brothers dipped into the local pool of talent and found replacements for the rhythm section that were more than adequate to the task. I recall coming in before the music started on a weekend night, getting a beer, and then wandering over to check in with Sonny and pitch in with a helping hand if needed. Art had a big Leslie speaker hooked up to his organ and those speakers swirling silently in their cabinet before the show were sort of hypnotic to me. On this occasion there was a storm warning—a hurricane was brewing up in the Gulf and there was a good chance that it was headed our way. The clouds scudding overhead were ominous and the air was so heavy you could practically weigh it in your hands. But this was New Orleans, and the show must go on. Something about those hurricane-threatened evenings added an extra intensity to the party, like it was our duty to stare down the storm, to double down on the jam just to let it know that we weren’t intimidated.

The Brothers kicked off their set, smooth and deep as usual, and the intensity just built over the course of the evening. As with many New Orleans music clubs, there was no set closing time and the band did their two (or three?) usual sets and then came back for more. The dance floor was jam packed and the band was laying down the groove like never before. It was two o’clock, three o’clock, four o’clock in the morning and we just danced and danced and the Brothers wouldn’t let up. By the end of the third (or fourth?) set the dance floor was an inch deep in a slobber of sweat and spilled beer. People were popping gators down in the gray slop and all the shit was falling out of their pockets but no one cared. Finally the Brothers finished their last song but the audience just kept on going. The Brothers picked up cowbells and tambourines and filed off stage right to the side door, which had been open all evening to try and let some cooler air in. Led by Cyrille the band danced out onto the Napoleon Avenue neutral ground followed by the rest of us, singing, chanting, clanking beer bottles together. We continued to dance for another 20 minutes or so, following Cyrille and Art as they called out the Indian chants that we all knew so well. Finally it came to a halt and everybody just fell onto everybody else, hugging and laughing and slapping sloppy wet high fives. I took off my t-shirt and wrung it out and the sweat just poured from it like I had been wearing it in the shower. It was amazing, epic, and it was ours—the 50 or 75 or 100 or however many people who had stuck it out to the end. I got on my bike and rode home in a joyous delirium, soaked down to my socks.

The hurricane in the Gulf caught the vibe, thought better of it, and veered away from New Orleans at the last minute. We were spared once again.

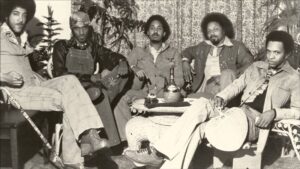

The Radiators at the Dream Palace

The Radiators at the Dream Palace

New Orleans, circa 1978-’79

Like the Nevilles, the Radiators arose from the ashes of another great New Orleans band, the Rhapsodizers, who I loved dearly. The Rhapsodizers featured my friend and personal hero Clark Vreeland on guitar and vocals and the great Becky Kury on bass and vocals, and it was hard to imagine that anything could be any better than that. When Rhapsodizer keyboardist/vocalist Ed Volker, guitarist Camile Baudoin and drummer Frank Bua hooked up with Reggie Scanlan on bass and Dave Malone on guitar and vocals it proved to be a fortuitous hybrid of the soulful psychedelic tinged funk of the Rhapsodizers with a higher energy dual guitar delivery that was mind-boggling for a young six-string wannabe like myself. These guys really could shred and I was in awe of how great they were, watching them from inches away, trying to figure out how they managed to do that thing they did.

Like the Nevilles, the Radiators were weekend regulars at Tipitina’s, but they also played frequently at the Dream Palace, back of the Quarter in the Faubourg Marigny on what was then sleepy Frenchmen Street, about a block and a half off Esplanade. I saw them play in both venues, but there was always something special about seeing the Radiators at the Dream Palace. The DP had a wild, loose psychedelic vibe about it—there were murals on the ceiling and up and down the walls depicting the planets and the stars and the constellations and airplanes and skydivers and morning glory vines and a nude man and a woman outlined in stars above the bar. It had this laid-back trippiness to it that just seemed to add something special to a Friday or Saturday night with the Radiators, and it quickly became my preferred venue to see them at. It wasn’t as convenient as Tip’s and if I couldn’t pitch in with a group of friends that included someone with a car I had to either take the streetcar down to Canal Street and walk through the Quarter, or ride my bike. But it was always worth it. Nights at the Dream Palace even had their own theme song: ‘Tropical HotDog Night’ by Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band: Tropical HotDog Night! Like two flamingos in a fruit fight! Everything’s wrrrong but at the same time it’s RIGHT! Step out of darkness into striped light, STRIPED LIGHT!

The Radiators nights at the Dream Palace tended to be druggy more than boozy—psychedelics being the order of the day (or the decade, for that matter)—and there were more nights than I can remember that turned into days, stumbling out into the oyster gray dawn, to shamble down Frenchmen to pile into the car or the back of the truck or onto the bike and dribble home, brains melting out of ears, utterly spent and beat and not worried about it because we were young and poor and felt that we had nothing to lose. It was all about dancing back then and we danced and danced and danced with one another, with whoever was there, with the band, with ourselves. You just had to move. Sometimes we stopped for breakfast at the Hummingbird, thrilled and scared shitless to face the terrifying waitresses who put up with absolutely no shit from anybody.

The Radiators never disappointed. We knew and loved all the songs, some of which, like ‘Suck da Heads,’ had become like anthems to us. These Dream Palace adventures were some of the best nights of my misbegotten youth.

New Orleans, 1978

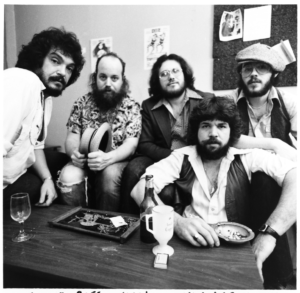

After the Rhapsodizers called it quits Clark Vreeland regrouped with a different cast and a new cache of songs that were generally shorter, more jagged and less funky than what he had done with his previous band. This new group was Room Service and they were influenced by the emergence of punk that was just barely beginning to make inroads into the New Orleans music scene. Clark paired up with Spencer Bohren, who shared duties on guitar and vocals, backed by Marc Hoffman on bass and Tommy Conga on drums. They later added Webb Burrell as a third guitarist/vocalist but I never saw that particular lineup of the group. That’s Room Service pictured at the top of the page as I knew them, from left to right–Tommy, Marc, Spencer and Clark, with Clark taking first prize in the band ‘Skinniest Tie’ competition.

Clark was a godlike figure to me when I was a kid—I worshipped the guy. He was an amazing player and an extremely charismatic guy onstage and off, but very elusive, moody and cryptic. You can read more about Clark in the tribute that I wrote in these pages back on January 1, 2014. I loved the Rhapsodizers—perhaps the greatest homegrown rock and roll band to ever come out of New Orleans—and markedly different though they were, I loved Room Service as well. Clark was a unalloyed genius in my book and if he was going to sit onstage at Tip’s and read the New Orleans telephone directory I would been right there in the front row.

As it was, the balance between Clark and Spencer as front men of the group was an unusual but fortuitous one. Clark’s unusual vocal style ranged from the laconic to the snarly—there nothing conventional about it. Spencer had a smooth bluesy/soulful delivery that had served him well over the course of a long career and the juxtaposition of Clark and Spencer’s singing, not to mention their guitar styles, was at the core of Room Service’s appeal. The instrumentation was sparse and largely revolved around Clark’s thick psychedelic-tinged stylings, coaxed out of a vintage Strat run through some sort of distortion pedal and an MXR Phase 90 and then through a 1960s 4 x 10 Fender Concert amp. Clark had a guitar sound and a style unlike anyone else—Hendrixy, but not in any sort of obvious or imitative way—and he was a master of feedback and whammy bar technique.

I went to see Room Service whenever I had the chance but on one occasion in 1978, as described in my tribute to Clark, I attended a show at Tipitina’s with Denise Charbonnet and her cassette boombox. We recorded the entire show that evening and decades later, after Clark’s untimely passing, I digitized the recording, remixed it, and burned it onto CDs. I caught up with Spencer one night a few years ago in New Orleans when he was playing at Chickie Wah Wah. I gave him copies of the remixed recording from Tip’s and he mused that Room Service was always amazing in rehearsals but tended to fall apart onstage. If they were better in rehearsal than they were that night Denise and I recorded them at Tip’s I’d be amazed, but then Spencer would know. Room Service blew my mind whenever I saw them and they still do whenever I listen to that show. The Meters, and then the Nevilles, laid down the essential New Orleans funk and the Radiators covered the rocking dance party end of the spectrum, but Room Service lurked down at the dark end of the street where things were a bit edgier and mysterious. Clark was and remains one of the primary influences on my musical sensibilities and I hope that his memory will live on forever in some fashion or another. Sadly, Spencer passed away just over a year ago within weeks after his last JazzFest gig. I don’t know whatevert became of Marc and Tommy, but Room Service was one of the truly great bands from a golden age of music in New Orleans.

The Rolling Stones and the Meters

The Rolling Stones and the Meters

LSU Assembly Center, Baton Rouge, June 1, 1975

1970. No more Beatles. Shit. What’s a budding adolescent rock and roller and hardcore Anglophile to do? I surveyed the musical landscape and, somewhat by default, became a Rolling Stones fan. At first, just a fan, but by 1975 a full-on fanatic. I was pretty well obsessed with the Stones, 24/7 365, but when they swung through the South on their 1972 tour they bypassed New Orleans. In 1975 they forsook the Crescent City again, probably for lack for a suitably sized venue (Superdome—too big and not quite finished yet/every other place—too small) and instead headed to Baton Rouge and the Assembly Center at Louisiana State University. This was to be the kick off of their 1975 American tour and current accounts describe the two June 1 Baton Rouge shows as ‘warm up’ gigs. I guess the band figured that in a backwater like Baton Rouge no one would care too much if they sucked. Regardless of what anyone called it, it was the actual Rolling Stones. This, for me, was tantamount to the gods descending from Olympus to shine their light on us mere mortals for a fleeting moment. It actually strained credulity to think that Mick and Keith would actually be there and that I would also be there in the same room with them.

I went with my mom to our neighborhood A&P Grocery Store and acquired a money order for $20, or some such extortionate amount, which I then sent off somewhere to acquire my ticket—or perhaps that was for two tickets, as my girlfriend was going with me. In due time the ticket(s) arrived and the date approached. I arranged to take the Bus to Baton Rouge (all props to Lucinda Williams) with several friends and we met up at the depot on the appointed afternoon, girlfriend Sandy in tow. Her dud of an older brother was a student at LSU and once we arrived we went to hang out at his apartment in married student housing before the show. He had a job on campus as a security guard and I recall that he advised us not to ‘shoot up’ while at the arena—the quotation marks literally hanging there in the air of his dumpy little apartment. Shoot up?? I was 15 for crissakes!! I had only gotten stoned a handful of times and this bonehead thought we were junkies or something! I recall Sandy and I laughing in his face and assuring him that we had left our GIANT STASH of HEROIN at home.

The atmosphere inside the Assembly Center was electric and the fact that the Meters were opening the show was beyond astounding to me. These guys lived in my neighborhood! The Meters danced onstage in ‘funky undertaker’ attire and laid down a solid set, but the crowd was impatient. Joints and pipes were being passed around, as was typical of the day, and within short order I was high high high. During the intermission I wandered back to go to the bathroom and ran into José and I nearly cried I was so happy to see him. When the houselights dimmed again I could scarcely contain myself. Aaron Copland’s ‘Fanfare for the Common Man,’ in all of its percussive brassy glory, pounded through the PA at earsplitting volume. Through the scrims that had been lowered around the lotus flower-shaped stage I could see movement as a wash of purple haze came up. The Copland ended and the opening chords of ‘Honky Tonk Women’ blasted out. The scrims rose and there they were in a blast of white light, maybe 30 or 40 feet away. Jagger was wearing a loose sort of a sort of Scaramouche-ish striped pajama ensemble. Keith, then well into the depths of his addiction, looked noticeably more raggedy and worn than in ’69 and ’72. Ron Wood was onboard to replace the recently departed Mick Taylor, though he was still officially a loaner from Rod Stewart and the Faces at this point. Billy Preston, of whom I was a big fan, was on keyboards and backing vocals. The band sounded pretty sloppy and Mick seemed to be into some sort of rookie hazing mode with Wood and Preston.

Truth be told, I can’t remember much about the show, but I learned a few important things: Arena shows generally suck; the Rolling Stones were actual human flesh and blood human beings and were already on the decline; and Sandy was a pain in the ass. I saw the Stones in concert two more times after that (the Stupordome in New Orleans, July 1978, and at the Sun Bowl in El Paso in November 1994) and by 1994 they had become pretty much of a caricature of themselves—the world’s greatest Rolling Stones tribute band. I firmly resolved that the El Paso gig was to be my last arena/stadium show, and it was. But that 1975 concert was a watershed moment in my young life—my first experience of big time rock and roll. I remain very much of a Meters fan and not so much of a Stones fan. You gotta know when to call it quits, folks.

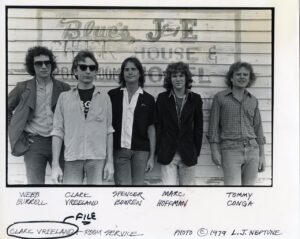

LSU Assembly Center, April 11, 1978

Back in Baton Rouge once again, but not by bus. The Superdome had been open for over two years by this point, but it was still too big for most bands and the LSU Assembly Center remained the best fit. I had seen Led Zeppelin there the year before (I can’t remember hardly anything about that show, and therefore it’s not on this list) and the Who had played there in late 1975, but I didn’t have my act together to make it. This time around it was Bowie and he was touring behind the release of Heroes and Low—two of his greatest albums. I had fallen headlong into Heroes when it had been released the previous year. It was different, genuinely strange, but it had pulled me in and wouldn’t let go. I didn’t know quite what to expect in the way of a Bowie concert, so my mind was very much open that evening.

As I describe in my Bowie tribute posting in these pages (January 16, 2016), I had become accustomed to the sturm und drang theatrics of big rock shows and was expecting more of the same, but Bowie had other ideas. First of all, there was no opening act, no hurry up and wait bullshit. Bowie and the band had been milling about onstage, the house lights fully up, for maybe ten minutes or more before anyone in the audience even noticed that they were there. And indeed, they were just… there—standing around, chatting with one another, smoking cigarettes, like… normal people might do? As the audience began to realize what was going on, or wasn’t going on, the house lights dimmed and the show began. Yes, it was theatrical, this being Bowie after all, but it wasn’t bullshit theatricality. It was subtle and arty and very effective indeed. At one point the focus of the show shifted from the stage to the audience as spotlight operators high up in the lighting rig swept their beams out over the crowd. It felt good, inclusive, and, for a change, the sound was fantastic. It was loud but not pummeling loud like the Stones or Zeppelin, and I could hear everything. There was a lot to hear and the atmospheric instrumental passages from Low and Heroes were some of the best moments of the show.

This concert expanded my conception of what a rock and roll show could be like. It was the first truly great concert that I had ever seen in a large hall and it remains one of the best. Bowie was great, the band was great, the staging was great, the sound was great—it was a truly satisfying experience on just about every level and it fulfilled expectations of rock and roll that I didn’t even know that I had. What more can one say? It was the one and only time that I saw David Bowie in concert and it was enough.

Memorial Coliseum, Jackson, Mississippi, December 19, 1978

1978 was a heady year for concerts in my young life, I must say. Bowie in April, the Stones (with the Doobie Brothers and Van Halen) in July, and now the Dead in December. Now, let’s get one thing crystal clear: I was not a Grateful Dead fan at that time and I’m not really much of one today. In 1978 I didn’t own any of their records, I had never really listened to any of their music (by choice, anyway), and as a bunch of bearded, raggedy ass, tie-dye hippies they just didn’t appeal to my sense of style. I was into the Brits pretty much exclusively and the Dead, and Americana in general, just didn’t do it for me. When my roommate Ryan insisted that I HAD to go to this show I had expressed zero interest but he would not take no for an answer. So I figured, Eh, what the heck? Why not. I had nothing more pressing to do.

Our other roommate, Mondo Don, had a car so in we piled in for the three hour drive to Jackson. I don’t know how we afforded it but we had somehow booked a hotel room for the night at a Howard Johnson’s or a Holiday Inn or something near the arena so it was going to be a real excursion. We filed into the arena that evening to find a very low stage (maybe four feet) against one side of the round building. The place was pretty small and the crowd on hand filled most of the open floor but very little of the seating on the levels above that. There was no opening act and at the appointed hour the Dead emerged onstage looking just as shambling and rumpled as I expected.

Then they began to play. The sound was crystalline—it was like listening to a really great quality stereo system in your own home. I had become used to pummeling, murky, thudding sound in venues like the LSU Assembly Center, so this was a revelation. You could REALLY hear everything, every single nuance of the music, and the vocals were crystal clear. Amazing.

The band played for, I dunno, an hour and a half or so and I didn’t know a single one of the songs but it didn’t matter. We had brought some mood enhancing substances with us on this trip (trip—get it?) that were left over from the Rolling Stones concert at the Stupordome back in July. What we had done was to take a liquid form of a certain proscribed psychedelic substance and drip one drop each onto a bunch of Cheese-Its crackers. The Cheese-Its had been packed into a backpack with other survival items and in the insane feet-off-the-ground crush on the floor of the Stupordome they had been pulverized into Cheese-Its dust. The one-drop-per-cracker scheme had therefore become meaningless and there was no way to calculate dosage. Oh well.

But the band, the band was playing and we were getting higher and higher and everybody was getting higher and higher and the band kept getting better and better and the music was flowing and pulsing and LORD amighty, was I having a fantastic time! The Dead finished up ‘Supplication’ and the lights came up and I thought ‘Wow, that was amazing! These guys are incredible!!’ I turned to Ryan and said ‘Why didn’t you ever TELL me that Jerry Garcia was the most amazing guitar player in the world??’ Ryan gave me a knowing look and said ‘I thought everybody knew that!’ How had I missed out on this? This was astounding new information—mind boggling! And it turned out that the show wasn’t even half over yet—this was just an intermission! An intermission at a rock concert? What the fuck?? I went out into the hallway surrounding the arena and bought myself a Grateful Dead baseball cap at the merchandise stand. I didn’t even own one of their records and here I was actually buying Grateful Dead schwag!

There had been a group of yobbos up in the stands to the left of the stage during the first set, whooping and boogying and jumping about, waving a Confederate battle flag and bottles of Jack Daniels around. I was perplexed by this—did they think they were at a Lynyrd Skynyrd concert or something? Was there so little to do in Jackson that whatever the gig was these folks would show up and go all Gone With the Wind apeshit regardless of who was playing? When the band filed back out onto the stage for the second set we looked around and those people were gone. Perhaps they thought the concert was over and went home? We looked around the hall and it seemed as though about half the people who had been there for the first set were gone. There were maybe 1,000 or so of us left, maybe less. As the band began to play and no crowds of people came streaming back into the arena from the hallway outside Ryan and Mondo Don and myself and all the folks around us moved way up close to the stage so that now we were maybe 15 or 20 feet back. With the stage as low as it was we were practically looking straight into the band’s eyes.

Again, I hardly knew any of the songs but I couldn’t care less. The music just got more and more amazing and the band’s telepathic communication with one another began to expand outwards into the audience. My spine began to limber up and and I felt this amazing pleasure center down in my nether regions begin to reach up towards another one that was glowing at the base of my skull. The magic Cheese-Its had taken full effect by now and Ryan and Mondo Don and I and everybody around us began to move with the music. The music flowed and then it rolled and swerved and then it gathered together with a sort of irresistible forward momentum and shifted into a higher gear like a locomotive running flat out, smooth and seamless on a bed of liquid steel. I looked up at Jerry Garcia who was now right in front of me. He was playing his Wolf guitar and looking down over the top of his omnipresent aviator shades, looking straight out towards me. He was like a wizard, a magus, and I realized that he was in complete control, subtly directing every nuance of the music, all the energy from the band was flowing through him and out into the tiny crowd. Garcia peered out at the crowd over his shades as he had done countless times before and I looked into his eyes and thought ‘Yes! I get it! I got you!’

The glowing centers of energy at the base of my spine and the base of my skull started to extend towards one another and I realized that I had to line them up just right. I was moving with the music and I began to shift my posture in tiny increments and, sure enough, I could feel the vertebrae began to align, one after another. The music kept building and I kept moving. I was concentrating with great intensity on this alignment but the music was one and the same with it. Finally I felt the last segment of my spine fall into alignment and this amazing bolt of energy shot up and down. This actually happened, Gentle Reader(s)—I shitest thee not. Okay, I was tripping my balls off, no doubt about it, but it felt totally amazing and I felt totally in synch with the music, with the band, with the crowd, with the UNIVERSE maaaan! I thought to myself, ‘Holy SHIT! I’m having an actual Grateful Dead experience!’ So this is what all those patchouli drenched hippies following the band around the world had been blathering on about for all these years!

Eventually the music ended and the lights came up. I had been utterly and unexpectedly transported to a whole other dimension and my mind had been boggled in the best possible way. My karma had not run over my dogma, but rather had pulled over and the dogma got in the karma and they drove off together and lived happily ever after somewhere in hills above Big Sur. Noted New Orleans musician and aficionado of all things musical and mystical, Al Frisbee, was standing behind us and I recall saying to Al ‘Is it like this EVERY time??’, to which he replied, ‘Oh no–you were lucky, this was a reallllly good one.’

Back in New Orleans, I ran out and bought several Grateful Dead albums. They sucked. I got rid of those and bought a couple of others. They sucked too. Finally I honed in on ‘Working Man’s Dead,’ ‘American Beauty,’ and ‘Europe ’72.’ Now these albums didn’t suck. They were actually pretty great, and there were a few parts of ‘Europe ’72’ that kinda sorta approximated what I had heard in Jackson on that Tuesday night in December—that locomotive on the liquid steel tracks. It was there in songs like ‘Jack Straw’ and the ‘China Cat Sunflower/I Know You Rider’ medley—I could feel that vibe and I can still feel it and remember what it was like to this day. But the rest of it… well, I think you get the picture. Eventually I loaned my Grateful Dead hat to some chick I met in the Negev Desert in 1979 and she didn’t give it back.

So that’s it. I saw the Dead once and it was amazing. In fact, it was so amazing that I never wanted to see them again. And I never did. So thank you, Jerry Garcia—that was one fucking beautiful show.

Thrilling stuff, right? Stay tuned, Gentle Reader(s), for The Shows That Mattered, Part the Deux, featuring Wilco, Black Flag, Saccharine Trust, Richard Thompson, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Lucinda Williams, Yo La Tengo, Gang of Four, David Byrne, the Ramones, and Jonathan Richman!

In the meantime, Be Strong, Keep Calm and Carry On.