11 Oct The Shows That Mattered, Part the Deux

Here, as promised, Gentle Reader(s), is the long awaited, much anticipated, second installment of the compilation of performances that have withstood the test of time and stand out as watershed musical events in the estimation of Your Humble Narrator. It’s quite the eclectic mix, ranging from the outer limits of avant grade jazz to the body slam of American hardcore in its bareknuckle heyday. And, praise be on high, it’s not over yet. There is sufficient material for a Part the Troisiéme, lawd hep us all, so stay tuned for the final installment in the days/weeks/months to come. Wilco, Saccharine Trust, Gang of Four, Lucinda Williams, Yo La Tengo and more are yet to have their day.

But for now, I give to you the Shows that Mattered, Part the Deux:

The Art Ensemble of Chicago

Kimo Theater, Albuquerque, NM, November 22, 1980

Growing up in New Orleans in the 1960s and ‘70s I was blessed with an extraordinarily rich musical landscape to sample from. By the time I was old enough to partake of the various offerings being presented at venues around the city, in the approximate mid-‘70s, New Orleans had entered into a period of musical renaissance that saw Professor Longhair retrieved from obscurity, the opening of Tipitina’s, and expanded appreciation of and opportunities for local musicians of all stripes.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to be a student at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts (NOCCA) in 1976-’77 and the jazz curriculum was the school’s elite program. The late, great Ellis Marsalis, patriarch of the city’s foremost jazz family, was the program’s director and his sons Wynton and Branford were both enrolled at the time. I was in awe of those guys—it was abundantly evident even back then that they were destined for greatness. The Marsalis family, like the Neville family, was a prodigiously talented crew—two genetically gifted dynasties that are still going strong to this day. However, being well aware that I possessed no innate musical talent of my own, I didn’t even bother to audition for NOCCA’s music program. I applied for and was accepted into the school as a drama student instead. The drama department was fucking lame—and I mean totally, pathetically lame. The instructors were such epic doofuses that I was actually embarrassed to admit that I was in the drama program. It was a total waste of time, but it was a fairly innocuous and amusing waste of time and it kept me out of regular classes for half of the school day, so well worth it despite the shame.

All of this is to say that I had a reasonably good grounding in the concept of improvisational music by the time I strolled into the KiMo Theater that evening in November, 1980. Albuquerque was not known as a hotbed of jazz talent but the New Mexico Jazz Workshop had nonetheless expanded my horizons by presenting artists such as Sun Ra and his Arkestra, Ornette Coleman, Art Pepper, and on this memorable evening, the Art Ensemble of Chicago. I didn’t know a damn thing about the Art Ensemble, but my boss Jim Reagan was a jazz aficionado (and an NMJW board member) and he was adamant that this was a rare opportunity, not to be missed. I took his advice.

This concert featured the classic lineup of the group that came together in 1970 with Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman on saxophones, Lester Bowie on trumpet, Malachi Favors on bass and Famadou Don Moye on percussion. In addition to their musical prowess the group was known for embracing a degree of theatricality in their performances. Lester Bowie, who seemed to preside over the proceedings in a subtle way, wore a white lab coat in concert which gave him a certain professorial air. Famadou Don Moye, Jarman and Favors all wore elaborate face makeup and African tribal garb. The members of the group engaged in bits of eccentric choreography and most of them switched from their primary instruments to a variety of others during the course of the concert. The AEoC didn’t shy away from displays of dazzling instrumental virtuosity—they were all superlative players but, as their name implied, they were focused primarily on the ensemble. The AEoC experience was actually very much akin to what I described in the preceding installment of this series with the Grateful Dead. Specifically, the group operated on a level of almost uncanny musical telepathy, best demonstrated in passages where they would go as far ‘out’ as one could possibly imagine, bouncing wild atonal polyrhythmic passages around the hall, seemingly all chaos and freeform madness, before suddenly snapping back into an airtight collective groove with a seamless precision that was utterly mind-boggling in its perfection. And all without any hint of a visual or auditory cue. The group’s intuitive interaction strained credulity, but they performed their miracles with such casual authority, such grace and style, that one almost had to laugh in astonishment. These cats could take you all the way out, to the very limits of improvisational music, and then bring you right back home again with a loose limbed, churchifying groove that made it hard to keep your hindquarters in your cushy KiMo seat. Much like the Dead, experiencing the Art Ensemble live was more than just a concert—it was an experience. And much like the Dead, as it turned out, their recordings were simply incapable of communicating the depth of this experience on vinyl. You simply had to be there.

So, yeah, it was an amazing concert. Stumbling out of the KiMo that night I felt as if I had been away on an unexpected journey to an unfamiliar place, somewhere I’d never been before. More importantly, the Art Ensemble had provided me with an answer to something that I had been grappling with for a while—a conundrum of sorts. Some friends of mine in the jazz community were adamant in their belief that jazz music could be a political expression, that it could even be revolutionary. I was rather incredulous about this. I felt that the music could perhaps be placed or presented in a political context, but without such context the music was too abstract and esoteric—even elitist, dare I say it—to express any kind of coherent political idea in and of itself. That night at the KiMo I realized that this kind of music was about freedom—total freedom—and that the concept of total freedom of expression, in any idiom, was a revolutionary one and therefore inherently political. It is for this reason that true artistic freedom of expression has always been regarded with suspicion, if not outright hostility, by authoritarian and fascistic regimes throughout history. Do you think there’s any remote chance in hell that the Orange Goblin could possibly dig the Art Ensemble of Chicago? Right. I thought not. The Art Ensemble of Chicago expanded my mind my that night and for that I will always be grateful (not Dead).

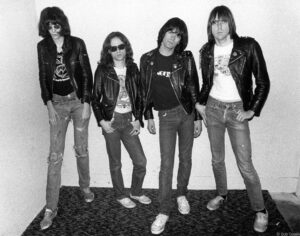

The Ramones & the Runaways

McAllister Auditorium, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, February 21, 1978

In February of 1978 I was 18 years old. I was a student at Tulane University and a rabid music fan, aspiring (and, as yet, highly incompetent) guitar player and voracious consumer of all available music press, Rolling Stone, Creem, Crawdaddy and Trouser Press being primary. I had been reading about the punk scene in New York and London for a while and a cover story in the October 20, 1977, issue of Rolling Stone had made a particular impression on me. The article, ‘Rock is Sick and Living in London’ by Charles M. Young was revelatory. The chaotic scene surrounding the Sex Pistols and their contemporaries seemed to be, and was indeed, worlds away from the realities of my teenage life in New Orleans. I found it fascinating, much as I had the initial reporting on Bob Marley and the Rasta/reggae scene in Jamaica a few years earlier.

Beyond aesthetic considerations, both the Sex Pistols and Bob Marley engendered an explicitly sociopolitical agenda that I found intriguing. For the moment, however, there was no way to know for certain what the U.K. punk scene was really all about because the music remained largely unavailable. The Pistols’ album Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols didn’t hit American record stores until November, 1977, so for the moment I just had to imagine. When the appointed day finally arrived I dutifully rode the streetcar uptown to the Mushroom to acquire my copy of the album, along with the Ramones’ Rocket to Russia, which had been released the previous week. When I was in the record store there was guy there decked out with spiky jet black hair, skinny black jeans and a metal-studded belt. I remember looking at this exotic apparition, thinking to myself ‘Wow!! That must be a punk!’

Despite their eminence as NYC punk standard bearers, the Ramones were essentially a pop band. Loud and fast and stripped down though the music was, it still adhered generally to pop conventions and songs such as ‘Rockaway Beach,’ ‘Do You Wanna Dance’ and ‘Sheena Is A Punk Rocker’ were little more than a short stone’s throw away from Buddy Holly, Bo Diddley and the Beach Boys (did the kids in New York really bring their surfboards to the Discotheque Au Go Go??). According to members of the Ramones, the ascendancy of the Sex Pistols and the massive amount of publicity they generated—the vast majority of it negative—created confusion in the public mind, who lumped them all together in a toxic stew of nastiness and nihilism. The Ramones felt that this impacted their band and its chances for mainstream popularity. Now, I was there and I was then, Gentle Reader(s), and while the Pistols and the Ramones were indeed both considered as being within the broader context of ‘punk rock,’ it didn’t take a genius to figure out that they had very little in common.

From what I had read about the Sex Pistols I fully expected Never Mind the Bollocks to be an unlistenable explosion of incoherent, anarchic noise. But when I lowered the needle into the grooves something completely different emerged: An expertly produced, very competently played, high energy rock and roll album with no shortage of great songs. And when John Lydon snarled ‘We MEAN it, maaaan!’ in ‘God Save the Queen’ it sounded like, well… like he really fucking MEANT it. That kind of directness and of-the-moment intensity was something I hadn’t quite heard the likes of before. The only things I could compare it to were songs like the Stones’ ‘Satisfaction’ and the Who’s ‘My Generation,’ but those anthems of disaffection were several years ahead of my time. Bob Marley and the Ramones and the Sex Pistols were very much of the now. Even though I was relating to all of them from a substantial cultural and geographical distance (New Orleans being almost exactly equidistant from Kingston, Jamaica, and New York City) the impact was undeniable.

When it was announced that the mighty Ramones were coming to play at the venerable McAllister Auditorium on the Tulane campus, I didn’t hesitate. This was something that I simply could not miss. The Sex Pistols had actually played a show in Baton Rouge back in January on their notorious and abbreviated swan song U.S. tour, but I had no money, no car and nobody willing to front either to get me to the gig. It was so close and yet so far that it broke my heart, but such was my lot. But McAllister was a different deal—I could ride my bike there and as an actual Tulane student I could even get a discounted ticket.

The Ramones were certainly more than enough of a draw unto themselves, but the Runaways were opening the show. They had been the subject of a cover story in Crawdaddy the previous October (the same month as the Rolling Stone profile of the Sex Pistols) but their scene sounded rather questionable, like some sort of Kim Fowley/L.A. scam job more than anything else. Of course the Sex Pistols gleefully claimed to be a scam as well, but coming from them it seemed more like anarchic irony than anything else.

On the night of the concert there was a good crowd on hand, but it didn’t appear as though McAllister was full to its 1800-person capacity. My fellow attendees looked like a fairly typical New Orleans concert crowd, though there might have been a few more leather jackets and spiky hair dos than normal. One stylistically ambitious concert goer was sporting a ripped t-shirt accessorized with pieces of raw chicken affixed with safety pins, deftly combining cutting-edge fashion with the danger of salmonella poisoning.

The Runaways, so much as I can recall their set, exhibited little more than bar band level competence. They were intriguing, but not much more. Had they been guys rather than five comely teenage girls with an abundance of in-your-face attitude they probably would have been booed offstage. But at least I could say that I had been there to see little Joanie Jett before she went on to achieve rock & roll icon status.

When the house lights went down again and the Ramones took to the stage their sonic assault was genuinely bludgeoning in its volume. Breathtakingly loud. The only thing that I had ever heard that was anywhere near to equivalent was a full-blown top fuel nitro-burning dragster at Laplace Drag Strip. I was maybe half way back in the hall and I couldn’t imagine how those up front could bear it.

The boys slammed from one song to the next with scarcely enough time for DeeDee to scream “ONETWOTHREEFOUR”—no twiddling about, no stage banter, just business. Johnny and Dee Dee’s hyperkinetic downstrokes-only playing style was the essence of anti-virtuosic, or at least so it seemed. Try playing that way for more than a minute—it’s incredibly difficult. The overall effect of the onslaught wasn’t ‘Hey, cool—it’s the Ramones,’ it was more like “HOLY MOTHER OF GOD!! IT’S THE FUCKING RAMONES!!!!!” It felt like I was the brat being beat on with a baseball bat, like I was the one receiving the shock treatment. The relentless pummeling was over in about 40 minutes. I could scarcely walk straight when I left the auditorium and my ears rang like fire alarms for the better part of a week afterwards.

I had never experienced anything quite like this. While it was undeniably appealing on a variety of levels it was sort of like observing some sort of an exotic hybrid, like the two-headed calf in the side show at the county fair or some sort of lab experiment gone wrong in an unexpected but entertaining way. I could kind of relate, but only in the abstract. And that pretty much summarized my relationship with ‘punk,’ or whatever it was that the Ramones were: I was definitely interested, sometimes engaged, often amused, but never much more than an observer. Or facilitator. And this from someone who actually ended up playing in a punk band a couple of years later. While I was not exactly ‘faking’ it, I was never more than a stand-in for the real thing, and that was plainly obvious to one and all. Especially me. Be that as it may, I did see the Ramones—the 100% original Ramones: Joey, Johnny, DeeDee and Tommy—in their glory days. I don’t think my ears have completely stopped ringing ever since. Seriously.

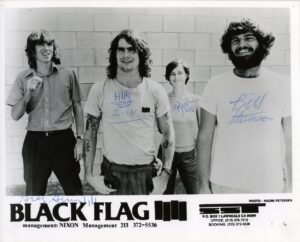

Black Flag, St. Vitus, Tom Troccoli’s Dog

Casa Armijo, Albuquerque, NM, December 3, 1984

By 1984 Black Flag had managed to accrue an impressively fearsome reputation as violent, misogynistic, nihilistic, riot-inducing hooligans. Their music, which I was only marginally familiar with, resembled something more akin to the anarchic blast of atonal noise that I had been expecting when I had brought home my copy of ‘Never Mind the Bollocks.’ The mayhem of their concerts was already the stuff of legend and the cops on Black Flag’s home turf in southern California had taken notice and were responding with state-sanctioned violence and mayhem of their own. The band’s lead singer, Henry Rollins, had become a poster child, or perhaps a pinup boy, for the new strain of hardcore that was giving fits to Ronnie Reagan-era buttoned-down America. It was a rather intimidating profile.

This was back in the early heyday of Bow Wow Records, the esteemed vinyl (and eventually CD) emporium founded earlier in the year by my boss Andy. The original Bow Wow location was a narrow storefront just off of Central Avenue on the hipster-ish strip east of the UNM campus. It was maybe 16 or so feet wide and maybe three times as deep. Not a large space by any means, but in the earliest days of the store it was the venue for a number of shows, including punk outfits like Red Kross and TSOL and electric rake virtuoso Eugene Chadbourne. I have no idea how many people crammed into the store for some of those gigs, but things got pretty insane and it was a bit of a miracle that the place didn’t get totally trashed.

In November, 1984, Bow Wow was approached by SST Records about presenting a Black Flag gig. Despite some initial hesitation along the lines of ‘What the fuck are we getting ourselves into??’ we decided to go for it. It was obvious that it would be foolhardy in the extreme to try and present the band in the store. Through some questionable avenue or other we were alerted to a place called Casa Armijo, a decommissioned schoolhouse just outside the city limits in Albuquerque’s South Valley. The place was essentially bulletproof—it was already a dump and there was nothing to break. Just a floor, a ceiling and some walls. And it was in the county, not the city, so should we have any issues with the local gendarmerie it would be the sheriff’s department and not the Albuquerque city cops—ostensibly a point in our favor. Given a choice, avoiding the attention of law enforcement in general was obviously the preferable option.

So the word went out, the tickets went on sale, and, as per usual, hosting the bands (the lineup included two additional SST acts—Tom Troccoli’s Dog and St. Vitus) fell largely to myself and a few of the Bow Wow faithful who had a bit of floor or sofa space to spare. As the one and only Bow Wow employee, I agreed to house the headliners.

On the afternoon of the gig I drove down to the hall to check on the load-in and put a face on Bow Wow. When I arrived at Casa Armijo I found a crowd of tattooed, long haired dudes humping the PA gear into the hall while a small group of local fans stood around and gawped. Tom Troccoli’s Dog was essentially a noise rock trio consisting of a couple of Black Flag roadies with Flag’s guitarist/founder Greg Ginn on bass. St. Vitus was a doom/sludge metal band from L.A. Everyone had long hair, tattoos, and looked like they hadn’t had a shower in a couple of weeks. I spotted Henry Rollins and introduced myself. I got a brief, solid handshake and ‘Howya doin, man’ before he threw himself back into the load in. In this crew there was no distinction between the musicians and the roadies, something that I could well appreciate.

Later on in the afternoon Henry was sitting in one of the old school desk/chairs that had been left in the back of the hall, head down, scribbling with great concentration in a notebook. A local fangirl was desperately trying to get his attention by making a ruckus and enacting a highly dramatic meltdown over some trivial issue. None of this routine was proving successful in penetrating Henry’s laser-like focus. Growing desperate for some acknowledgement, the girl went over and grabbed his left arm and yanked on it. Henry’s head snapped up, he threw up the arm that the girl had grabbed, knocking her backwards. She landed on her ass and skidded a few feet across the floor. Everybody in the whole room just froze. Henry glared at the girl, who was stunned but unhurt, then snapped his head back down and continued scribbling.

Note to Self: Inadvisable to bother Henry while he’s writing.

By showtime the hall was filling up and a highly anticipatory buzz was palpable. Tom Troccoli’s Dog and St. Vitus did their respective sludgy things to varying degrees of engagement from the crowd, but very few of those in attendance had bought their tickets to see those guys. When Black Flag—Henry on vocals, Kira Roessler on bass, Ginn on guitar and Bill Stevenson on drums—finally took the stage the anticipation had reached a fever pitch. Stories had been circulating about the epic beatdowns that resulted when aggro fanboys, intent on proving their studliness to their homies, provoked Henry at gigs. I couldn’t imagine why anybody with half a brain would push their luck like this—the guy was built like a brick shithouse and he had this ferocious intensity that was rather, well… ‘intimidating’ doesn’t quite do it justice.

When Flag cranked up their first song the volume was pretty mind boggling but the most incredible thing was the energy—Henry’s intensity first and foremost, but that of the rest of the band too. Ginn’s guitar style was like some deranged blend of Hendrix, James ‘Blood’ Ulmer and just pure noise. He played one of those heavier-than-shit clear Perspex Dan Armstrong guitars straight into an Ampeg bass stack—a solid state bass stack—with no distortion pedals or anything, relying on sheer volume for all the drive. Stevenson was a monster drummer and Kira was a strong bassist and threw herself into the set with a gusto that belied her pixieish stature.

The audience whirled and smashed and thrashed and slammed into a maelstrom of cyclonic proportions, arms and fists and feet flying around with a violence that made the punk gigs at Bow Wow seem like church bake sales in comparison. Moshers hurled themselves off the stage, twisting and backflipping. If anyone lingered for more than a couple of seconds on the lip of the stage one of Flag’s fearsome roadies would dash out to launch the interloper back into the scrum.

Presiding over it all was Henry. Glistening with sweat, his long black hair whipping around, dressed in a pair of minute black jogging shorts and nothing else, the mic cable wrapped several times around his fist like some sort of gladiatorial appendage, a dervish of muscles, hair and tattoos. I was standing at the back, trying to protect my ears, and every now and then some dude would come spinning out the back of the crush with blood gushing from a broken nose or a lacerated scalp. When the band launched into anthemic songs like ‘My War’ the insane whirlwind of bodies whipped upwards into a higher gear of madness and it felt like the goddam roof might blow off of old Casa Armijo.

Despite the chaos, the band was amazingly tight. They were obviously very well rehearsed and no one missed a cue, fluffed a note or seemed distracted by the insanity swirling around them. It was pounding, pummeling music that seemed perpetually on the brink of spiraling completely out of control, but somehow holding together. It was, quite frankly, astounding: That much chaos and that much precision, simultaneously. The Ramones might as well have been playing Bach concertos in comparison.

When it was finally over my brain felt like it had been put into a blender, doused liberally with speed-laced LSD, pureed, and then poured back in through an ear. Mercifully, the sheriff’s department had deigned not to descend upon us to shut the gig down and billy club us all into oblivion. Amazingly, no one seemed to have been grievously injured, although I do seem to recall doing a pass around the hall with a mop to sop some of the more alarming puddles of blood.

Somehow the experience had managed to transcend the noise, the chaos, the aggression, the testosterone-mad moshing. It amounted to something greater than its various frenzied components, something that—dare I say it—seemed to approximate Art. There was a higher level that I hadn’t been anticipating—a level that aspired to an exhilarating communal experience, some kind of sublime madness that we had all played a part in creating. Who’d a thunk it? I certainly hadn’t thunk it.

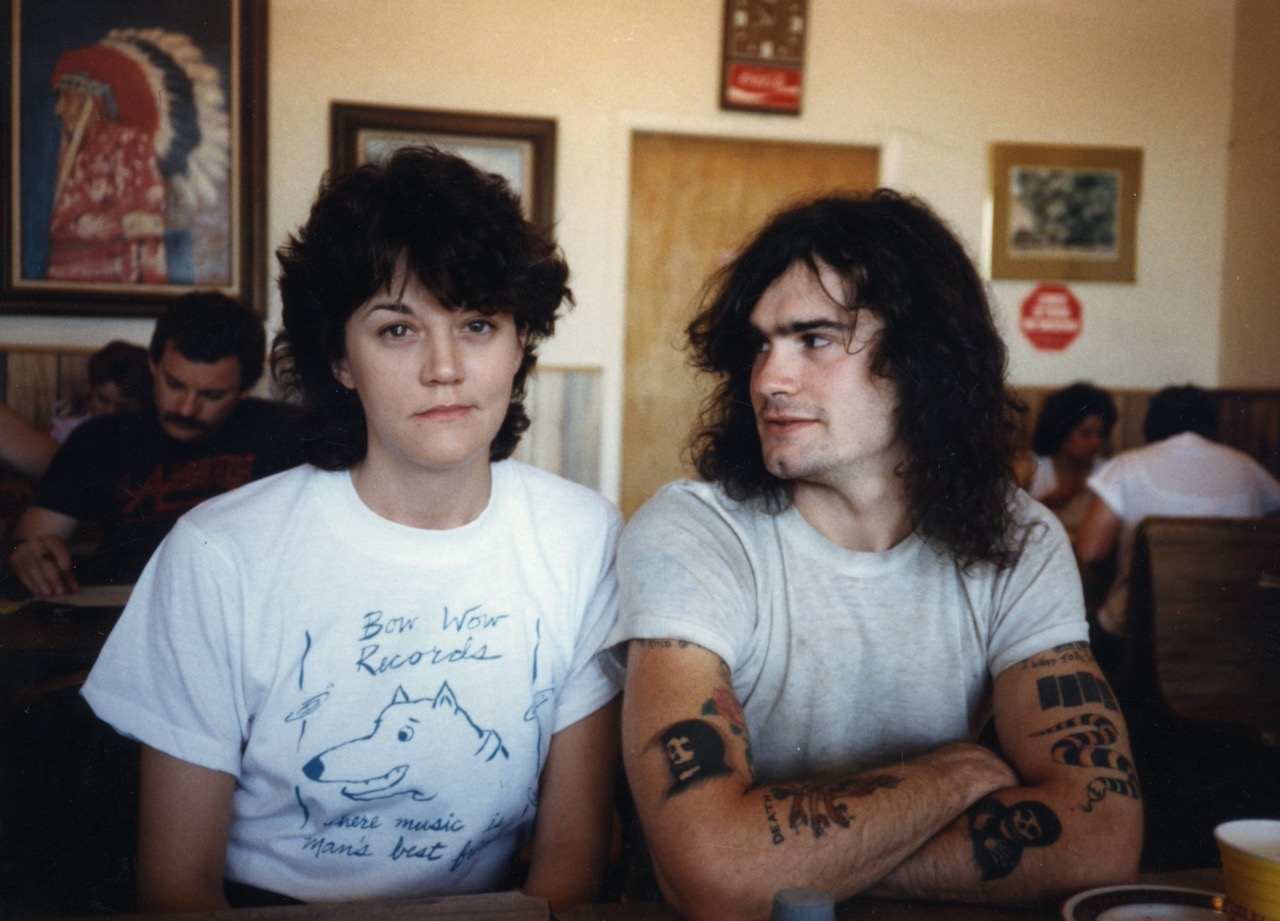

Henry helped hump the gear out of the hall and back onto the truck. Along with some of the band members and crew he climbed into a van and they followed me over to my place near the UNM campus to crash out. Henry looked around at the records and books spread around the apartment and said ‘This is your place? This is your stuff?’ I replied in the affirmative and he said ‘We gotta talk.’ Which we have been doing, periodically, ever since. About a month and a half later I presented one of Henry’s early spoken word gigs to a curious audience of about 25 patrons in the back of the Living Batch Bookstore. (The photo atop this page depicts the terrifying Henry and bemused New Orleans homegirl Tanya Coyle at the Frontier Restaurant in Albuquerque, 1985.)

Bow Wow staged another Black Flag concert at Casa Armijo in May of ‘85, this time with the amazing Minutemen on the bill. Flag were still a force to be reckoned with but the band was beginning to disintegrate. Bill Stevenson was gone from the drum chair, Kira had adopted heavy black makeup, fingerless gloves and other gothy accoutrement. It just wasn’t the same. Flag hung it up a little over a year later and Henry went on to fame and fortune as, well, Henry. I later went to a couple of Rollins Band shows and I’ve attended a good number of Henry’s spoken word performances, which are reliably quite awesome, but that first Black Flag gig in 1984 remains one of the watershed musical experiences of my life. In terms of pure energy and musical intensity I honestly don’t think I’ve ever experienced its equal.

Jonathan Richman

Bow Wow Records, Albuquerque, NM, ca. 1985/‘86

And now for something completely different.

Whatever one might have thought about Bow Wow Records, we were nothing if not diverse in our presentations back in the day. On one hand, we were host to pretty much every SST band that came down the pike, and there were a lot of them. On the other hand we put on concerts by Tractor, Timbuk3, the aforementioned Eugene Chadbourne, Camper Van Beethoven, Alex Chilton (a true horrorshow, that one), Roger Miller (of Mission of Burma), Peter Holsapple (of the dB’s), Brian Brain (with drummer Martin Atkins of PiL), Downy Mildew, and a variety of local bands. Once the word got out that Bow Wow had tossed its proverbial hat into the concert promotion ring all manner of indie artists looking for a convenient stopover betwixt and between Phoenix and Lubbock, or Denver and El Paso, gave us a call. Eventually Jonathan Richman landed on our doorstep.

Like a lot of people, I was familiar with Jonathan’s early material with the Modern Lovers, but less so with his later solo work. Having eschewed his raucous rock & roll roots, Jonathan had unplugged his guitar and was now doing solo acoustic gigs. He now espoused his intention not to play anything loud enough to ‘hurt a baby’s ears,’ in stark contrast to his Velvet Underground-inspired music of the early ‘70s. Okay… a bit odd, but whatever.

Jonathan’s first Bow Wow show or two were presented at the store’s more expansive digs on Central Avenue, a few blocks west of the original location. In terms of low impact these shows were minimal in the extreme: No amps, no drums, just a basic PA system, a couple of microphones and Jonathan and his guitar. The man himself showed up with his suitcase, a backpack and his guitar, and that was it. Instead of camping out on the floor of my apartment I think he slept on Andy’s sofa. Andy had small children and Jonathan related well to kids.

Jonathan wanted to buy a vocal mic to travel with so I took him across the street to a store that sold sound equipment. I introduced him to the proprietors and they sold him a good quality Sennheiser mic. As we walked back to Bow Wow Jonathan said to me, “Hey, you didn’t have to introduce me as ‘Jonathan Richman,’—you could have just said ‘This is my friend Jonathan.’” ‘Uhhh, okay, sorry!’ I said, although it was plainly obvious that the guys at the store didn’t have the vaguest notion of who Jonathan was. He was a funny guy, and I don’t mean entirely in the ‘Ha ha’ funny sense.

Quirky though he was, Jonathan was still an amusing chap to hang out with and we spent a fair amount of time together over the course of several Bow Wow sponsored gigs. In October of 1985 I took Jonathan to a Kenny Rogers/Dolly Parton concert at the UNM Pit where, on some perverse impulse, I introduced him to New Mexico governor Toney Anaya who was sitting nearby. Both parties were politely befuddled. When Jonathan had a 4 AM bus to catch to his next gig we spent the evening hanging out at the Nines, Albuquerque’s premiere gay/new wave dance club. I introduced him to some of my friends and, to the great enjoyment of all and sundry, he danced like a complete madman until closing time.

I was initially uncertain about what to expect from Jonathan in concert. Was he going to play nursery songs and bore everyone to death with infantile ramblings? Could one solitary oddball with an acoustic guitar possibly be sufficient to keep an audience entertained for an entire hour? The answers were, emphatically, ‘No’ and ‘Yes.’ Jonathan turned out to be a genuinely engaging and charismatic performer, capable of cranking out danceable minimalist rock & roll (and he loved to dance onstage) as well as moments of emotional intimacy in which he held the audience rapt in the palm of his hand. The highlight of those early shows for me was his performance of the song ‘Affection’ from his 1979 album ‘Back in Your Life.’ This was Jonathan at his best, singing about love and the deficit thereof in the uniquely vulnerable manner that was his trademark. In those moments, when he took it down to the core, you literally could have heard a pin drop. He had this way of holding his guitar out from his body as he played, looking into the audience with this pleading expression that only the most terminally jaded and cynical individual could possibly resist.

Bow Wow presented Jonathan several times over the course of the ’80s but after the first couple of shows he added other musicians, eventually settling on the duo format of himself accompanied by drummer/sidekick Tommy Larkins. They were always enjoyable gigs but the intimacy and impact of those early solo shows were the pinnacle for me. In recent years Jonathan has gotten progressively more… eccentric (I think that’s the polite word for it) and the last show I saw was sort of like an improvisational attention-deficit cabaret act.

The upshot of this trip down memory lane is that the two most captivating and charismatic performers that I encountered during the fertile heyday of Bow Wow Records were absolute polar opposites: Henry Rollins and Jonathan Richman. Sort of like Mister Rogers and Jim Morrison. Two more disparate artistes one could scarcely conceive of, but all part of life’s rich pageant, I suppose. And we’re all the richer for it. Thank you Henry, thank you Jonathan.