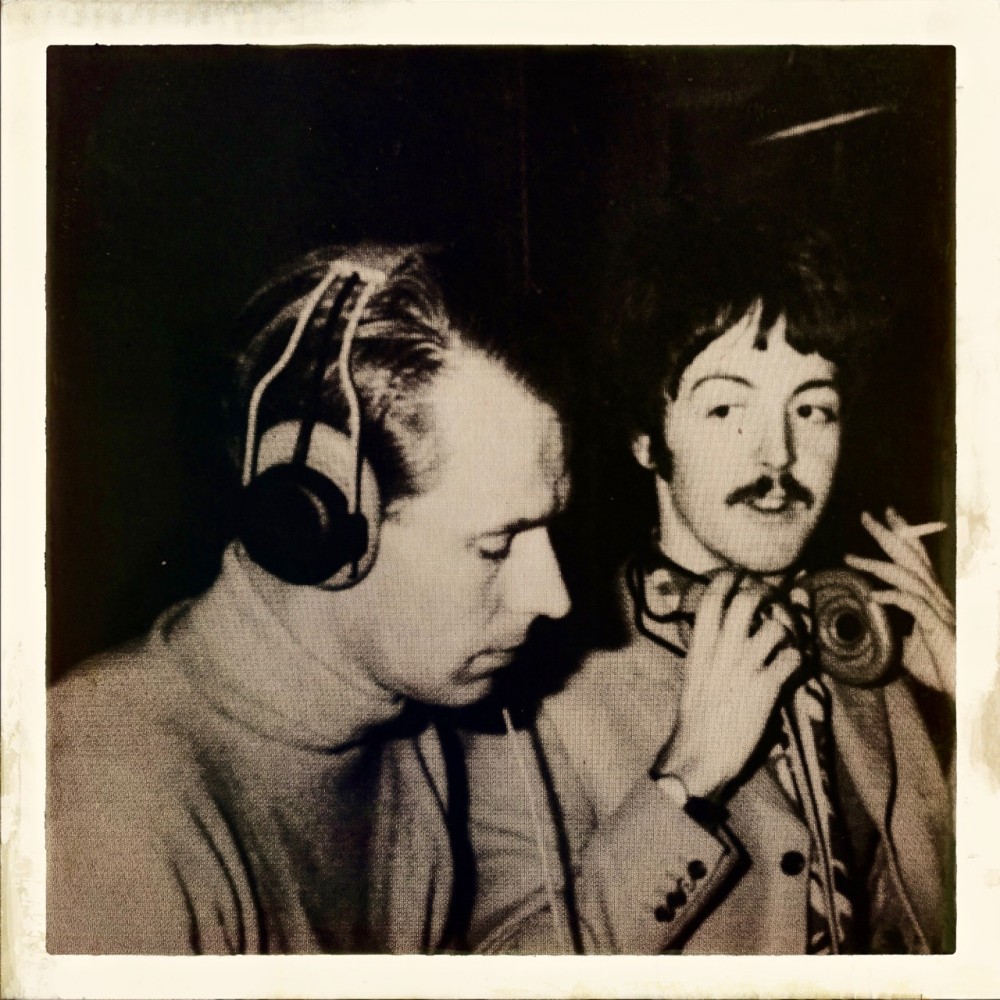

15 Mar The Other George

As I’m sure you’re already aware, Gentle Reader(s), the great Sir George Henry Martin passed away last Tuesday at the age of 90 years. To all reports, Sir George’s was a life very well lived. He was respected and beloved by a great many people, not the least of whom was a group of four lads from Liverpool whom Martin met at Abbey Road studios in London on June 6, 1962. After he signed the Beatles to EMI’s Parlophone label George Martin went on to produce all of the group’s albums, save for the last (‘Let It Be,’ for which he functioned in a production advisory capacity). Beyond his groundbreaking work with the Beatles, Martin was a key figure in the evolution of the professional recording studio from a stuffy, formal laboratory environment (which in Martin’s early days still involved studio engineers wearing ties and white lab coats) to a venue for free form sonic experimentation and creativity. There are other producers who emerged from the 1950s and ’60s whose names are as well known as those of the artists with whom they worked (Sam Phillips, Quincy Jones, Berry Gordy and Phil Spector), and some artist/producers whose visions for their own compositions incorporated the possibilities of the studio as a primary element (Brian Wilson, Jimmy Page, Todd Rundgren and Prince prominent amongst them), but George Martin was the true revolutionary. Be that as it may, it took time for the full measure of Martin’s contributions to become acknowledged: In the Beatles section of the first edition (1976) of the epochal ‘Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll’ George Martin doesn’t even merit a mention.

In his classic biography of the Beatles, Hunter Davies describes our hero thusly: “George Martin always seems light years away from the Beatles in class, tastes, and background. He is tall and handsome in a matinee idol sort of way, with a studied prep-school master manner and a clipped BBC accent.” He joined the air wing of the Royal Navy in 1943 at the age of seventeen and served until 1947 after which he studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. In 1950 he went to work for the Parlophone wing of the British media conglomerate, Electric and Musical Industries—EMI. Martin made his reputation at EMI with novelty records and recordings of comedy groups, working with people such as Peter Ustinov, Anthony Hopkins, Peter Sellers, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. His quirky sense of humor was apparent when, a few weeks before the Beatles entered his life, he produced a proto-electronic dance single—Time Beat backed with Waltz in Orbit—under the pseudonym ‘Ray Cathode.’ Whatever their cultural differences or shared interests might have been, it turned out that George Martin and the Beatles had chemistry, and that chemistry was in itself an extension of their genius. They were the right people in the right place at the right time and together they created great and timeless art.

The early Beatles albums, from ‘Meet the Beatles’ through ‘Help!’ (in the American discography), remained fairly conventional recordings—straight guitar, bass, drums and vocals, with little in the way of distinctive or innovative production values. In the stereo mixes (typically done as an afterthought at that point in time) the vocals are panned hard to the right and the instruments to the left in the manner characteristic of the day. But with the release of ‘Rubber Soul’ in late 1965, George Martin and the Beatles started to hit their stride. The instrumentation began to expand to include exotics such as sitar (Norwegian Wood) and the presence of keyboards in a mode other than straight ahead Little Richard/Jerry Lee Lewis-style rock n’ roll pounding (In My Life). ‘Rubber Soul’ was recorded during the period in which the band had begun to back away from touring and focus on studio work. It is also the first Beatles album to feature songs written exclusively by band members.

The Beatles’ next release, ‘Revolver,’ marked their true break with the past and the beginning of the maturity of their careers as composers and studio artists. Martin’s contributions became more prominent in landmark songs such as Eleanor Rigby with its beautiful double string quartet arrangement—nary a drum nor guitar to be found—and the brass solos and ensemble work on Yellow Submarine, For No One and Got To Get You Into My Life. But the direction ahead is fully manifest in Tomorrow Never Knows—two minutes and fifty-eight seconds of dense psychedelic studio fug, sound effects, compressed drums, double-tracked vocals run through leslie cabinets, backwards guitar and stereo panning. This is rock and roll that is meant to be listened to, with full attention, with headphones, preferably while in an altered state of consciousness. Tomorrow Never Knows is a true studio composition—it could never be reproduced in a live concert setting and was not intended ever to be. The studio itself had become the band’s instrument and the producer was no longer just a technician but a true collaborator in the alchemical process of utilizing and expanding technology to create art.

The full flowering of the band’s partnership with Martin was to come the following year, in 1967, with the release of ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’ and ‘Magical Mystery Tour.’ ‘Sgt. Pepper’s’ is, of course, the most celebrated and best known rock and roll album of all times, and rightfully so. Not only did it incorporate groundbreaking songwriting, packaging and production, but it was conceived of as a cohesive whole rather than a just a collection of songs. ‘Magical Mystery Tour,’ released later the same year, was more of a collection of songs but it contains Martin’s finest moments as a producer (and those of Martin’s engineer, the great Geoff Emerick). In addition to being brilliant songs, Strawberry Fields Forever and I Am the Walrus are lush sonic soundscapes that incorporate some of the most sophisticated studio techniques to appear on any recording of popular music to date. The juxtaposition of John Lennon’s psychedelic/surrealist visions with some of Paul McCartney’s purest, most brilliant pop (I Am the Walrus transitions to Hello, Goodbye, Strawberry Fields Forever transitions to Penny Lane) illustrates the exceptional range of the band’s songwriting, not to mention the continuing emergence of George Harrison as a composer.

The so-called White Album, Abbey Road and Let It Be were to follow—all beautiful and masterful albums in their own rights, but the band had begun to splinter and the glory days of the Lennon/McCartney songwriting partnership were essentially history. The only Beatles album for which George Martin did not receive a full producer’s credit, Let It Be, is also the only Beatles album to have been substantially reworked—re-released in 2003 as Let It Be… Naked with the majority of Phil Spector’s production and orchestration stripped away. Such a thing would be unthinkable with any of Martin’s productions. George Martin was the progenitor of the celebrity producer/artist—a concept that is now well established. Producers from Brian Eno to Timbaland are known worldwide for their status as masters of the recording studio and collaborators with the artists with whom they work. Of course this would have happened eventually with or without George Martin, but like the Beatles themselves, the breadth and depth of his influence upon the world of popular music is incalculable. Rest in peace, Sir George.