05 Mar Les Garçons du Printemps

Every spring I look forward to it, but not quite in the manner of, say, a holiday or a birthday—I’m well past the point of looking forward to those. Neither fully secular, sacred nor profane, it is more the initiation of a process than a specific event. Nonetheless, elements of spirituality, rebirth, renewal, and a quasi-mystical sense of nostalgia are commonly associated with it. Much misty-eyed, overwrought commentary has accrued to it over the years. Why stop now?

Despite the histrionics, this annual ritual could not be more democratic, more quintessentially American, more beautifully ordinary in its extraordinary way. It is the return of baseball season—spring training in early March in Florida and Arizona, and the regular season a month later across the continent. It is a feeling like no other and I love it dearly. In the immortal words of the fictional plucky Dominican, Chico Escuela, ‘Béisbol been berry berry good to me.’

Growing up as I did in a town that was severely deprived of professional sports—and that includes the first several decades of Saints football—baseball seemed like something relatively foreign and remote. Charlie Brown and his gang played it. You could watch it on broadcast TV (with more regularity then than you can now), and just about every kid knew the name of the big stars of the day: Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Sandy Koufax, Roberto Clemente. I had a bat and a glove and a baseball. I had a jacket with the logos of all the major league teams sewn onto it. But the last professional baseball team to play in New Orleans closed up shop the year I was born. Limited though my exposure to baseball was, I was still somehow aware that it was America’s game.

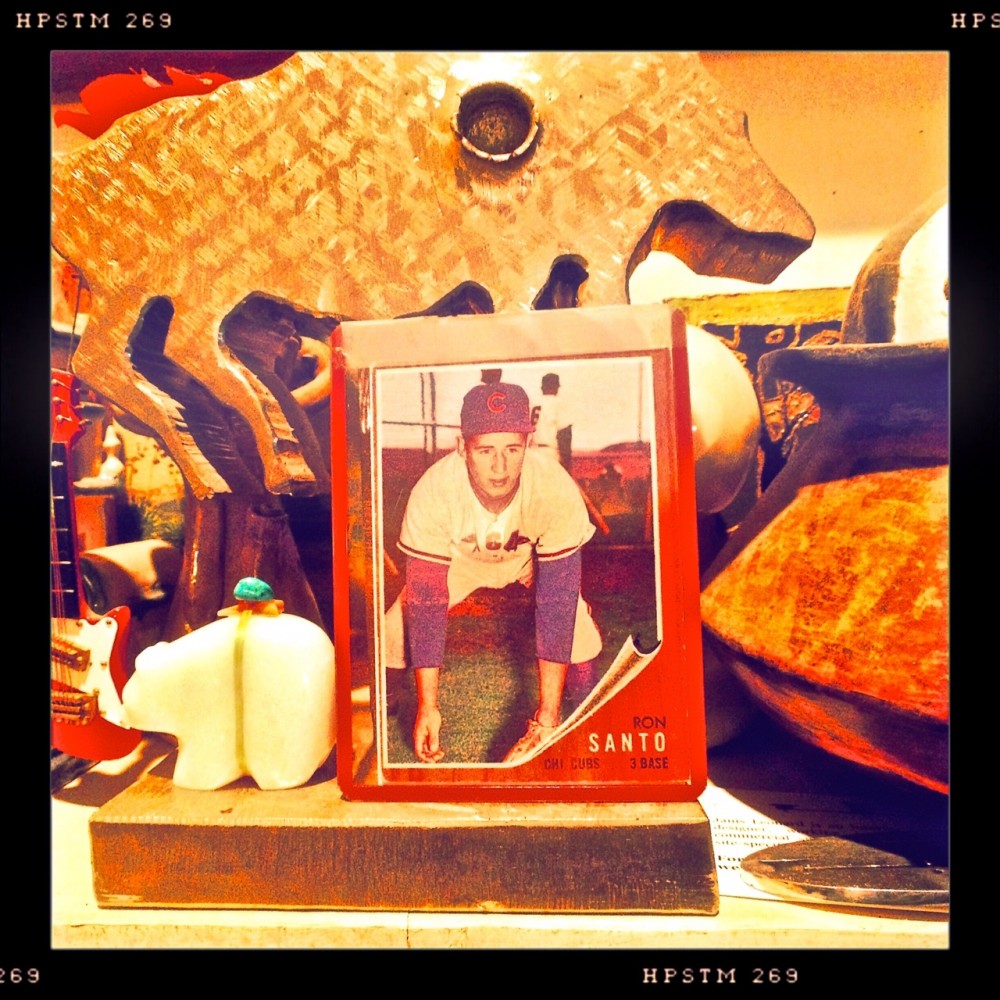

The closest place to New Orleans where professional baseball was played was Houston but I recall no affinity whatsoever for either the obscenely named Colt .45s nor their successors, the Astros (as the team was thankfully rechristened in 1965). But then, in 1969, while visiting relatives in Chicago, my grandfather took my father, my brother and myself to Wrigley Field. It was the first professional sporting event I had ever been to. I’m sure that it made little impression on me at the time, but it was a banner (though ultimately futile) year for the Cubs. The players on the field would have included all-time team greats and future Hall of Famers Fergie Jenkins, Ron Santo, Billy Williams, and the recently departed Ernie Banks. The manager was another future Hall of Famer, the legendary Leo Durocher. I can’t recall who the visiting team was or even who won the game, but for many years afterwards I kept my grandfather’s meticulously annotated score card. Grandpa purchased miniature Louisville Slugger bats and lightweight plastic Cubs batting helmets for my brother and myself (much to the horror of my mother who, not unreasonably, anticipated the two of us beating each other over the head with the billy club-sized bats).

Regardless of who won or lost that game, the hook was in. It took a while for the seed to fully take root (I was rabidly anti-sports in my teenage years), but when it did I proudly embraced my adopted team: I was a Cubs fan. In the sports world this is pretty much equivalent to declaring yourself as an adherent of Esperanto or being president of the Oklahoma chapter of the Green Party: A lifetime of futility and disappointment beckons.

This prospect never bothered me. In fact, I consider it to be a badge of honor. It’s easy to love a winner—everybody does. Sure, it might be nice to be a Yankees fan—they are, after all, the winningest sport franchise EVER, in ANY sport, ANYWHERE. But so what? There’s something beautiful and, dare I say it, noble about loving the underdog. About being the underdog. Somebody’s got to lose—why not the Cubs? For over a century now, despite the occasional, hopeful flash of brilliance, they’ve proven themselves to be very very good at it.

Yes, it’s nice when your team wins. It’s a good feeling, no doubt about it. But much more than winning, I just love baseball. I love that it’s a sport that largely remains the product of a 19th century agrarian society. It is not a sport in which violence has any sanctioned place. It is a sport in which the balance between individual achievement and the coordination of team effort has found the most pleasing and provocative balance. It is the only major team sport (except for its cousin, cricket) that has no clock. Those of us in contemporary society are generally under enough time pressure as it is, and the relentless tick-tick-ticking down of the football/basketball/hockey clock or the ticking up of the soccer clock seem too much like work to me.

I think a lot of it can be traced back to my childhood immersion in the world of Charlie Brown and Peanuts. Charlie Brown’s own baseball team almost always lost. His baseball hero was the hapless Joe Shlabotnik, a player who was sent down to the minors because of his .004 batting average. Perhaps Joe’s lowest moment was when, as a minor league manager, he signaled for a squeeze play when his team had nobody on base. Shlabotnik got fired but Charlie Brown loved him nonetheless. I can relate to that.

Efforts to pull baseball from the 19th into the 21st century have been gathering momentum in recent years. Instant replay was introduced last season and purists, like myself, grimaced. Central to baseball is that human judgement—and therefore human error—is an inevitable, if not integral, component of the game. The strike zone, for instance, is invisible, idiosyncratic, and entirely conceptual. Rather like the Holy Ghost. To accept that it even exists requires an act of faith.

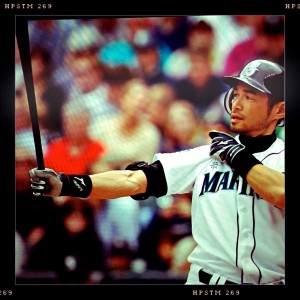

This season, MLB has finally succeeded in adding a clock to baseball. I shudder yet again. The clock does not specifically regulate the length of the game, but rather a variety of intervals during the game. Most notably, the league is trying to reduce the amount of time batters spend going through their pre-swing rituals or just wandering thoughtfully around home plate. By requiring batters to keep one foot in the batter’s box between pitches (or at least pitches not swung at) the notion is that the pace of the game will pick up. I wonder how Nomar Garciaparra’s wondrous catalogue of intra-pitch tics and tweaks would fit into the new regimen? How about Ichiro’s deep knee bends and elegant slo-mo windup-and-sleeve-tug? I guess we’ll just have to find out.

I shall have to trust that, despite the appalling intrusion of chronographic devices, baseball will somehow manage to still be baseball. After all, in the early days of the game players didn’t even wear gloves. Batting helmets didn’t become mandatory equipment until 1970. But then no one in baseball ever died from obsessive tightening of their batting gloves.

Bottom line, I’m old school. A traditionalist. I still listen to most games on the radio—albeit via the internet. And it’s that sound—the sound of a baseball game on the radio—that means it all to me. Of course the days are getting longer and warmer, the trees are beginning to bud, but for many years it was Ron Santo and Pat Hughes’ voices coming through the airwaves on WGN radio. That was spring to me. The time when things begin again.