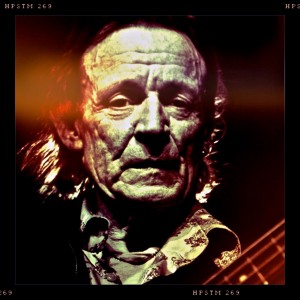

18 Nov Jack Bruce: An Appreciation

He was good. He was very very good—quite possibly the best in the opinion of more than a few people who were well placed to know.

Despite an eclectic five-decade-plus career in music, most people’s awareness of John Symon Asher Bruce extends from his two-year tenure as the bassist/lead singer of Cream. You had to be good to be in Cream—the best, in fact. That’s why the group was called Cream (and, thankfully, not Sweet n’ Sour Rock n’ Roll—a wisely rejected alternative moniker). You had to be able to hold your own with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker—not an assignment for the faint of heart nor tenuous of talent. Baker, who would, on occasion, assault and threaten to kill Bruce, said of him “He’s a fucking brilliant player—there’s no doubt about that.”

Jack Bruce was part of a pool of exceptional young musical talent that began to emerge in the United Kingdom in the early 1960s. The presence of large numbers of GI’s had served to introduce R&B, jazz, blues and early rock n’ roll to a restless generation yearning to throw off years of bland conformity and post-war austerity. Starting in 1961 groups such as Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, the Graham Bond Organization, and the Yardbirds began to attract significant audiences and attention. Between them, these four groups counted among their alumnus all three members of Cream, Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones, Cyril Davies, Aynsley Dunbar, Charlie Watts, Mell Collins, Dick Heckstall-Smith, Peter Green, John McVie, Mick Fleetwood, Mick Taylor, Harvey Mandel, Keef Hartley, John McLaughlin, Jeff Beck, Danny Thompson and others. Electrified R&B, blues and jazz were not sharply segregated factions on the London scene at the time and talented musicians such as Baker and Bruce were able to move back and forth between one genre and another with relative ease.

The evolution from the Chicago-style blues and R&B of Blues Incorporated and the Graham Bond Organization, in which both Bruce and Baker played, to Cream constituted a significant conceptual advance. The essential conceit of Cream was to take the electric blues idiom, add a tantalizing dollop of au courant psychedelia and chamber pop, and supercharge it to previously unexplored levels of speed, volume, intensity and improvisation. While the band’s studio output tended towards concise pop compositions, most not exceeding four minutes in length, in live performance Baker, Bruce and Clapton indulged their improvisatory abilities to the fullest. While Clapton remained firmly rooted in the blues idiom the rhythm section had an undeniable loose-limbed swing: Bruce and Baker were jazzers at heart. This relatively compact version of ‘Steppin’ Out’ provides an excellent example of the loose/tight swing that the band could bring to an otherwise straightforward blues instrumental.

Jack Bruce’s post-Cream career saw his jazz tendencies come to the fore in a string of highly regarded solo albums and group efforts that ranged from tightly composed proto-fusion to free form improvisation (some fine early Bruce jazz performances are captured in this otherwise ponderous 1969 documentary, ‘Rope Ladder to the Moon’). It’s hard to pay the bills with jazz, however, and periodically throughout the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s Bruce would return to blues rock with distinctly mixed results, complicated by persistent drug problems and progressively declining health. Bruce developed liver cancer and very nearly died from complications following a liver transplant in 2003.

By 2005 Bruce was well enough recovered to participate in a much-anticipated Cream reunion. A series of highly successful shows in London at Royal Albert Hall (locus of the band’s fairly lackluster 1969 ‘Farewell’ concert) and in New York at Madison Square Garden revealed a trio of musicians that, in some respects, fulfilled the promise of their youthful ambition. Clapton, Baker and Bruce were older, wiser, less self indulgent, and more generous with each other than they were in their 20s. What the performances might have lacked in intensity they made up for in beautiful, heartfelt playing and intuitive group interaction. The old dogs rose to the occasion admirably and, once and for all, showed the kids how it was supposed to be done.

A reasonably objective consideration of Jack Bruce against his bass playing contemporaries of the rock n’ roll world, class of early/mid 1960s, would seem to confirm that there are none, really, that rise quite to his level of musicianship, expressiveness and passion. And that’s without even taking into account his considerable abilities as a vocalist, composer and arranger. Bruce was best in class and any bass player worth their salt would readily admit as much.

Jack Bruce: 5/14/43 – 10/25/14. Rest in peace.