05 Oct Chocolate City Redux

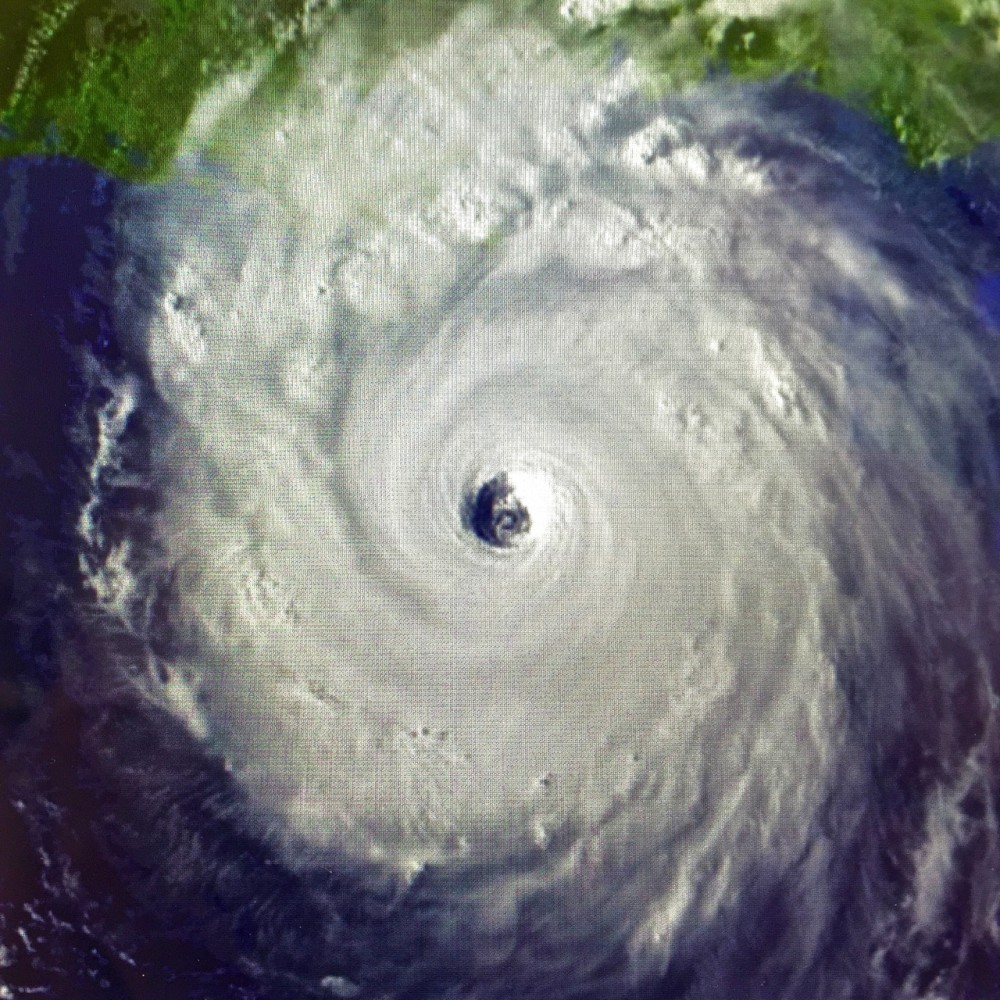

Not surprisingly, the arc of media fascination with New Orleans and all things Katrina-related has surged, peaked and quickly faded. The storm made landfall on the Gulf Coast on the 29th of August, 2005, conveniently providing the entire month for build-up to the tenth anniversary of the cataclysm. Media outlets around the country and around the world weighed in with reportage, retrospectives, editorials, polls, photo essays and then/now updates to assess the near-death experience of one of the world’s great cities and a decade’s worth of efforts to rebuild, renew and protect the City That Forgot to Care. The conclusions to be drawn present a decidedly mixed bag.

To a degree perhaps unequaled by anything that preceded it, the Katrina disaster unfolded in real time in front of the eyes of the world. The prognostications leading up to the storm’s landfall were dire and while the federal government seemed to be caught unprepared the media was fully entrenched. Unlike the terrorist attacks of 9/11 everyone knew the storm was coming. But hurricanes are notoriously unpredictable—they dodge and swerve at the last moment, stall over water and gain strength or move inland and lose energy rapidly. There was no way to know with any certainty exactly what would happen or what the extent of the damage would be. For a strange, brief moment it appeared that the worst had been avoided. The winds died down, the skies cleared, a collective sigh of relief… but then it quickly became apparent that things were going terribly wrong. There it was on television: My hometown, drowning in its own filth, its poor and dispossessed dying in their homes and in the streets, huddled on their rooftops and on overpasses, crammed into nightmarish conditions in the Superdome and the Morial Convention Center. The thought then and now remains the same: Is this America? How was this possible in the richest, most powerful country the world has ever known? I think Middle America was deeply shocked by what it saw but to natives and those on intimate terms with New Orleans, there was nothing new, unknown or unfamiliar other than the profoundly detached ambivalence of the Bush administration.

As an expatriate native New Orleanian, many people reached out to commiserate with me after the storm hit. I thought about how to explain my perception of what had happened and this is what I came up with. My simile for Katrina and its aftermath was based on the Bourbon Street party meter. To wit: On any given day or night of the week at any time of the year there is a party of some degree taking place on Bourbon Street. On an average weekday the party meter may read 2 or 3 on a scale of ten. On weekends the reading may go up to 3 or 4, perhaps 5 or more if it’s a holiday. If there’s a big concert or a sporting event in town—a bowl game or the Saints playing at the Superdome—the party meter may notch up to 7 or 8. When Mardi Gras season comes the party meter is slammed all the way up to ten and beyond. Things go totally off the hook and anything can happen. The point is, the party is perpetual and totally familiar—it just varies in scale and intensity.

The meaning of the party meter comparison with Katrina was that there was nothing that happened that was unfamiliar to those who know the city well. The breakdown of civil order, the corruption, the criminality, the violence, the failure of leadership, the failure of infrastructure, the harsh indignities of institutionalized poverty, the legacy of decades—centuries, even—of neglect and Forgetting to Care: All of it was known. When Katrina came and the lights went out and the water began to rise all the old and familiar woes went off the meter. Just a matter of scale and intensity. For example, flooding in New Orleans is a regular and expected occurrence—it happens to some extent just about any time the rain comes hard enough and long enough and the existing mechanisms can usually handle it. The failure of the levees and flood walls and the pumping systems after Katrina changed everything and transformed what had been a dangerous and damaging storm into an unprecedented man-made disaster. This is now established fact. It is the ‘hows,’ ‘whys,’ and ‘wherefores’ that are still being sorted out ten years later.

Even though most generalizations tend to fall short, some generalizations regarding Katrina and its aftermath have become established fact—in particular, this one: Those most affected by the storm and the flooding were/are disproportionally economically disadvantaged people and people of color. However, the so-called Sliver by the River—the neighborhoods bordering the natural levee along the banks of the Mississippi—are (or were) a highly mixed region, economically and racially. Some of the hardest hit areas in the city were in the middle class and upper middle class neighborhoods near Lake Ponchartrain. However, since Katrina the areas that have seen the most dramatic rebound are areas such as these. The combination of the economic advantages enjoyed by those living in these areas, very likely including more and better insurance, have been augmented by government initiatives such as the Road Home program and FEMA grants. Of course, not everyone is created equal in terms of having the fortitude to withstand barrages of bureaucratic bamboozlement, to provide reams of documentation, and to have the patience and faith required to navigate these labyrinthine processes. Attempting to steer through the maze while displaced and destitute certainly didn’t help improve the outlook for a lot of folks. For some, the road home was more of an obstacle course.

But what better than a bit of armchair anthropology in order to impart an injection of firsthand data. One recent September afternoon I dragged a chair out onto the front stoop and sat down with a beer and a book and waited for the world to pass by my door. And pass by it did. This neighborhood, the neighborhood where I grew up, was once predominately black and working class, but the non-motorized traffic up and down the street this afternoon was exclusively young and white. Clutches of tattooed hipsters on fendered townie bikes, a skinny young dad in a wife-beater toting a baby and accessorized with an airedale on a leash, lithe young lasses out for a jog with the labradoodle, practitioners of the Man Bun(!)—any and all of this would have been a) inadvisable and b) impossible to imagine just a few years ago (say, pre-September, 2005, give or take). But there it was, right in front of me on Laurel Street. Eventually my feet started itching and I realized that there was a swarm of minuscule mosquitoes attacking my lower extremities. Proclaiming my highly scientific sampling complete, I dragged my book, my chair and my beer back inside.

No doubt about it, New Orleans has changed. My neighborhood has changed. Some will argue convincingly that the change is for the better—young energy, the entrepreneurial spirit, revitalization, rejuvenation… gentrification? Others will argue passionately and just as convincingly that the changes are for the worse, that some portion of the essential soul of the city has been lost or at least sold off to the highest bidder, never to return. As for myself, I am old enough to remember the French Quarter in the 1960s. The old French Market, the Morning Call Coffee Stand, the fish market on Decatur, Battistella’s restaurant—all of it gone by the early to mid-1970s, when ‘renovations’ (overseen by Clay Shaw, nonetheless!) recalibrated the southern margin of the Quarter for optimal tourist appeal. The moment that the fish market was replaced by a t-shirt shop part of New Orleans did indeed die, never to return. Clay Shaw and the city fathers almost certainly considered it a mercy killing. New Orleans is a unique place and its special product is the city itself: New Orleans sells New Orleans. Tourists don’t buy fish pulled fresh out of the Gulf that morning. They do buy t-shirts, coffee mugs, little porcelain Mardi Gras masks, grotesquely oversized faux carnival beads and all the other miserable detritus flogged up and down the Quarter’s tourist thoroughfares. The influx of largely young, largely white and entrepreneurially-oriented newcomers may not be stimulating the trade in porcelain Mardi Gras masks but they are bringing something else to the table. As to whether what they bring will serve to benefit all parties remains to be seen (the old adage of ‘A high tide raises all ships’ hardly seems appropriate in this instance).

So, do my childhood memories of the French Quarter qualify as evidence of New Orleans Lost? I’m sure that there are many, including the bohemian crowd of my parents’ generation (the few remaining, anyway) who hearken back to an earlier day—the 1940s and ’50s—when life in the Quarter was cheap and easy. But there are quite probably those who decried my parents’ generation as decadent interlopers into what had been primarily a working class enclave, ala ‘A Streetcar Named Desire.’ The French Quarter is the most iconic, marketable and globally identifiable part of New Orleans, but New Orleans is much more than the Vieux Carré. The Ninth Ward and Uptown and Mid-City and Algiers and Gentilly and Ponchartrain Park are all New Orleans too and, to varying degrees, they all took the hit of Katrina—no one was spared. What was lost in those places? What has happened over the past decade to restore or replace what was lost?

Time again for a bit of hands-on investigation. With camera in hand I took to the streets to revisit some of the locales I had visited on my own and with the Commodore and Brother Dan Dog back in January ’06. I followed my original route out Carrollton Avenue, past the Archdiocese. The lot across the street from the Archbishop’s digs (illustrated as ‘Dresden on Carrollton Avenue’ in Chocolate City, Part the First) has long been cleared and now consists primarily of a verdant community garden. Further out, Lelong Drive at City Park still looks strangely denuded: The dense canopy of trees that once shaded the promenade leading up to the New Orleans Museum of Art was killed off by its extended soaking in salt water back in ’05 and the trees planted to take their place are still in their infancy. The City Park golf course is undergoing some sort of major renovation and the portion visible from Wisner Boulevard is massively dug up: Regardless of the vicissitudes of mere mortals, GOLF forges ahead!

The areas of Lake View and Lake Terrace that suffered severe ass whuppings back in ’05 have regained essentially all of their previous suburban splendor. Near the corner of Jay Street and Carlson Drive you don’t even need to squint to imagine that nothing significant has gone amiss in recent memory. A block away is the London Street Canal where the levee failed. The levee has been rebuilt as has the canal wall and the new locks are just to the south. This is one of the places where the Corps of Engineers will make its stand to keep Lake Ponchartrain out of the city when the next storm hits. Everything is green, placid and peaceful now in stark contrast to the scene I witnessed ten years ago.

Continuing on with my investigations, I headed south and east, down Elysian Fields to North Robertson and across the Industrial Canal into the Lower Ninth Ward. This was the epicenter of the devastation of the Katrina levee breaches in August, 2005, and by the time I saw the neighborhood four months later the only appreciable progress was that most of the streets had been cleared. Ten years later, the streets closest to the Industrial Canal are the ones that have become showcases for the work of Brad Pitt’s ‘Make It Right’ foundation: Deslonde and Tennessee Streets above North Claiborne are populated with brightly painted elevated homes, some in a traditional mode and others with a boldly postmodern vibe. However, just a couple of streets further east the show begins to lose steam and the landscape is dominated by empty lots inhabited only by the concrete slabs on which homes once stood, weed trees and tall grass.

Where are the people who once lived on these pre-Brad Pitt streets? Where are the people who lived in the now bulldozed housing projects? Apparently, the majority of them returned but something in the range of 80,000 displaced New Orleanians have not. One of the thornier questions in the orbit of post-Katrina consideration asks just how much of a tragedy this is. In an article in the August 24, 2015, issue of the New Yorker an article titled ‘Starting Over’ by Malcolm Gladwell addresses what being forced from their homes and from their hometown has meant to thousands of primarily African American New Orleanians. The article puts forth the proposition—backed by research and undoubtedly highly controversial to some—that, despite the devastation and trauma, the dislocation caused by Katrina was actually a blessing in disguise for some storm victims. Gladwell makes reference to the old Vietnam-era adage that sometimes the only way to save a village is to destroy it.

This is a sentiment reflected in my own ruminations regarding the situation I encountered back in ’06 and related in the Chocolate City Reports, Parts 1 and 2. How do you make right what has been wrong for decades, generations, even centuries—a system, a way of life, a culture—that knows no alternative or even that there were any alternatives beyond the known and familiar avenues of Forgetting to Care. There is a world out there beyond New Orleans and, for better or worse, the storm forced some folks to realize it for the first time. In some cases—apparently more than enough to be statistically significant—that realization has led people to a better life. It is a consideration between po-boys, crawfish, the irreplaceable vibe of familiar people and places and a chance for greater opportunity, higher wages, safer streets, better schools. I made my own decision 36 years ago, but I had then—and have now—the inestimable luxury of choice.

But the story is far from over. Things are still being sorted in New Orleans, day by day, minute by minute. The New Orleans Public School system (traditionally one of the worst performing school systems in the country) and its entire staff were significant victims of Katrina. The mixed blessings of what has risen up to replace it—the nation’s first all-charter school system—are still being quantified. Depending on whose version of the situation you adhere to, the all-charter revolution is either a craven corporate power/money grab and a dismal failure or a major step in the right direction. Perhaps it’s a question of which failure is the least objectionable: The dirty old familiar one or the shiny new one. Property taxes have doubled or tripled in the parish. The city has figured out that those who can afford to own property can help foot the bill for the recovery with, some might say, the added benefit of forcing out those who cannot afford to pay, thus opening up the availability of more real estate, expanding the city’s tax registers and stimulating the economy into the process. Rents have skyrocketed and, on average, renters can now expect to fork over 41% of median income for an apartment in the city. And those hipsters (or ‘fedoras’ as the Commodore refers to them) riding their bikes and walking their dogs up and down the street in front of my house, what do they portend? Are the carpetbagging millennials a blessing or a scourge? The overall number of murders in the city has dropped but in 2014 the murder rate was still more than three times the national average for comparably sized cities. There have been 130 killings in the city thus far this year with slightly less than three months left to go, but overall violent crime rates are reported to have dropped since their peak in the 2006 post-Katrina mayhem. Even more perplexing, a recent Kaiser Family Foundation/NPR survey reports that even the perception of the seriousness of the crime problem in New Orleans shows dramatic variability based upon who is doing the perceiving. A public outcry about escalating violence in and around the Vieux Carré led to extensive media coverage earlier this year which, in turn, led to Sidney Torres (the scion of a powerful St. Bernard Parish political dynasty who made a fortune carting away the detritus of Katrina) taking matters into his own hands… at least temporarily. This led to further consternation over the privatization of civic functions traditionally administered under the auspices of the public realm. Amy Goodman, NOLA homeboy Wendell Pierce and others devote an hour to mulling over the 10-year anniversary perspective in this clip from Democracy Now.

All of this begs the question, just WHAT the FUCK is going on down here?? The only sure answer is that it’s hard to be sure. Something is going on but exactly what it is and whether it’s a good thing or a not-good thing is clearly open for debate. One sure thing is that yesterday evening the Saints finally managed to blunder into their first victory of the season. For the moment, at least, there is joy in Mudville.