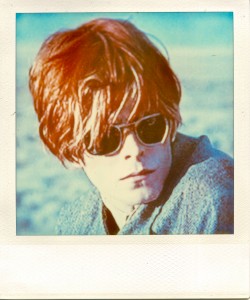

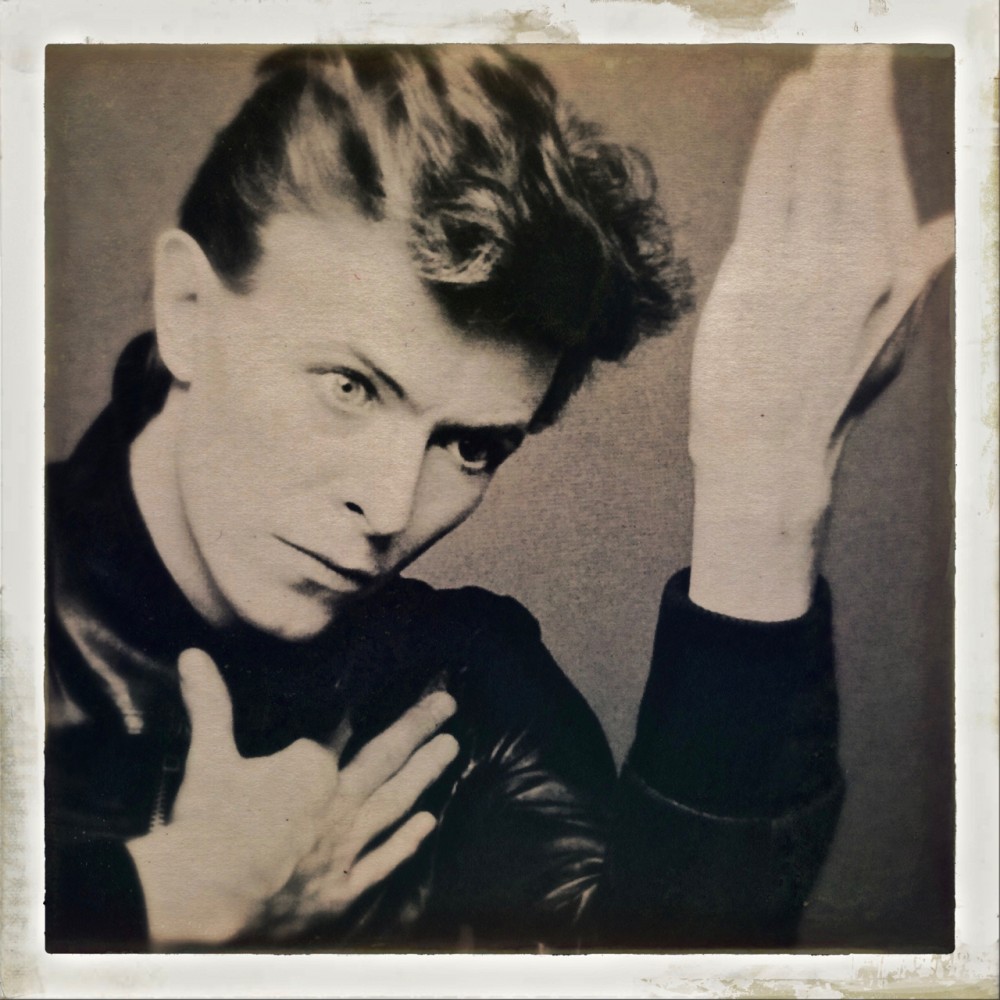

14 Jan Ashes to Ashes

Sometimes it’s difficult to know exactly how much someone means to you and how much impact they’ve had on your life until they’re no longer there. Unlike, say, the Beatles, I can recall a pre-David Bowie world. Therefore, I can say without reservation that the world was a much more interesting place with David Bowie in it. Now, sadly, we are in a post-David Bowie world and I am all too acutely aware of how much he meant to me. It would be cool to be able to relate some sort of direct, personal account of Bowie but, alas, I have none. We were once in the same room together, albeit quite a large room, and some people that I know knew him, rather well as it turns out, but for better or worse I never met the man.

For some reason, in the 1970s pretty much all of the big bands that came to Louisiana played in Baton Rouge at the LSU Assembly Center instead of in New Orleans. I suppose the reason was that the New Orleans venues were too small—at least until the Superdome was built and that was too large for almost everybody. The Rolling Stones, the Who, Led Zeppelin and others all played in Baton Rouge and on April 11, 1978, Bowie came to the Assembly Center for the tenth gig of his worldwide Isolar II tour. I had seen the Rolling Stones there in 1975 and the band had arrived onstage to the pounding kettledrums and stentorian brass of Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man. There was an elaborate pneumatic stage in the form of a lotus blossom (which wasn’t functioning for this, the first show of the tour) and a giant inflatable penis that rose out of the stage for the song Star Star (aka, Starfucker). When I had seen Zeppelin at the Assembly Center in 1977 it was the full-on laser beams/smoke/mirror ball/quadrophonic sound production at absolute pummeling volume. Therefore, when Bowie arrived the following year I was expecting something much the same.

Unexpectedly, Bowie’s stage turned out be a very conventional looking rectangular black box. There was no opening act and my friends and I milled about, checking out the crowd and chatting while we waited for the show to begin. The houselights were up and there were a few people wandering about onstage. I, along with everyone else, assumed they were just roadies and instrument techs and paid them no mind. At some point I noticed that one of the people onstage was Carlos Alomar, Bowie’s rhythm guitarist and band leader. Alomar was chatting with another person who was smoking a cigarette near center stage. It was Bowie. A ripple began to spread through the arena as people slowly realized that the band had already taken the stage. The audience started to clap and cheer, the houselights dimmed, and just like that the concert began. It was so unexpectedly casual and low key that it caught everybody by surprise. It was immediately apparent that this was going to be a different sort of concert experience.

The band opened with the moody instrumental Warszawa and over the course of a 22-song set delved deeply into the recently released Low and Heroes LPs. A bit past halfway through the concert, which included a number of rather abstract instrumentals, there was a seven song set from Ziggy Stardust that everyone went mental for. The staging was stark and minimal, the main feature being Dan Flavin-esque banks of white fluorescent lights that covered the back, sides and ceiling of the stage. The first time they were flashed on the blinding white light was breathtaking. During some of the slower, more contemplative songs white spotlights controlled by operators suspended in harnesses at the corners of the stage panned slowly across the audience. The effect was simultaneously thrilling and soothing, if that makes any sense. The absence of prototypical ’70s arena rock Stürm und Drang communicated a sensibility that was in stark contrast to the prevailing aesthetic of the day. This experience was more like—dare I say it?—art.

If you were to check back through the years of DJ Inky Matador playlists documented in these pages you would be hard pressed to find any that do not contain at least one David Bowie song. Usually more than one. This was not something that was even considered—there simply had to be some Bowie in every set. The Matador staff loves Bowie, the Matador crowd loves Bowie, everybody loves Bowie. How could you not? Now he has left us and I think it can be said with certainty that we will not see the likes of him again. He was an exceptional artist and in years to come we will continue to take the measure of his greatness. There’s not much more to say other than Thank You, David Bowie, for everything you gave us. It was a genuine privilege to share this planet with you for the time that we had. Your absence already looms large and you will be greatly missed.